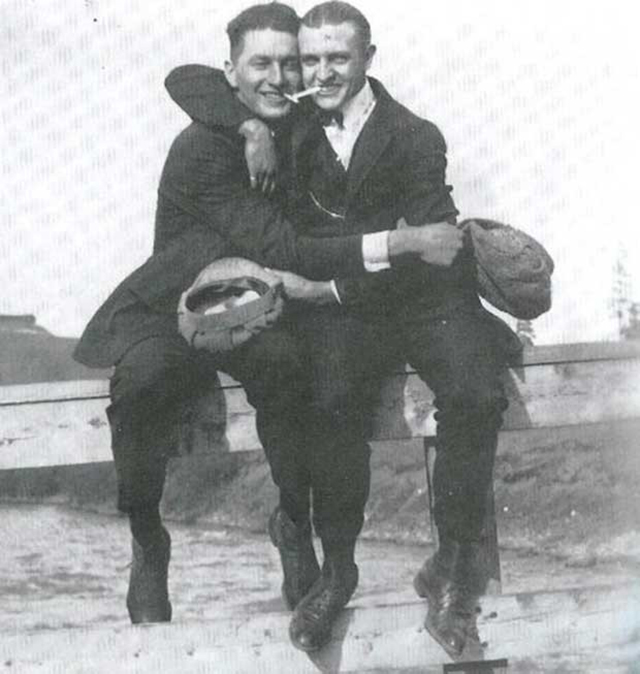

There was a time in America when two men pictured with their arms wrapped around each other, or perhaps holding hands, weren’t necessarily seen as sexually involved—a time when such gestures could be seen simply as those of intimate friendship rather than homoeroticism.

The photographs, spanning from the Civil War to the 1950s, reveal a lost world. They present men of different ages, classes, and races in a range of settings: posed in photographers' studios, on beaches, in lumber camps, on farms, on ships, indoors and out. They show men comfortably sitting on each other's laps, embracing, holding hands, and expressing their various relationships through countless examples of simple physical contact.

Men as Friends

From the Civil War through the 1920s, it was very common for male friends to visit a photographer’s studio together to have a portrait done as a memento of their love and loyalty. Photographers would offer various backgrounds and props the men could choose from to use in the picture. Sometimes the men would act out scenes; sometimes they’d simply sit side-by-side; sometimes they’d sit on each other’s laps or hold hands. The men’s very comfortable and familiar poses and body language might make the men look like gay lovers to the modern eye — and they could very well have been — but that was not the message they were sending at the time. The photographer’s studio would have been at the center of town, well-known by everyone, and one’s neighbors would having been sitting in the waiting room just a few feet away. Because homosexuality, even if thought of as a practice rather than an identity, was not something publicly expressed, these men were not knowingly outing themselves in these shots; their poses were common, and simply reflected the intimacy and intensity of male friendships at the time — none of these photos would have caused their contemporaries to bat an eye.

When the author of Picturing Men, John Ibson, conducted a survey of modern day portrait studios to ask if they had ever had two men come in to have their photo taken, he found that the event was so rare that many of the photographers he spoke to had never seen it happen during their career.

Snapshots

When portable cameras for the amateur photographer became more widely available, they allowed men to photograph themselves in a greater range of more spontaneous situations, and the practice of sitting for formal portraits together waned in the 1930s. The snapshots usually were developed by someone else who would have gotten a look at all of them, so again, these pictures were not likely purposeful expressions of gay love, but rather captured the very common level of comfort men felt with one another during the early 20th century.

One of the reasons male friendships were so intense during the 19th and early 20th centuries, is that socialization was largely separated by sex; men spent most their time with other men, women with other women. In the 1950s, some psychologists theorized that gender-segregated socialization spurred homosexuality, and as cultural mores changed in general, snapshots of only men together were supplanted by those of coed groups.

After WWII, casually touching between men in photographs decreased precipitously. It first vanished among middle-aged men, but lingered among younger men. But in the 50s, when homosexuality reached its peak of pathologization, eventually they too created more space between themselves, and while still affectionate began to interact with less ease and intimacy.

It’s not true that American men are no longer affectionate with each other at all. Hand-holding and lap-sitting are out, but putting your arms around your buddies is still common. Physical affection seems more common among high school and college age men, a time when friendships are closer, than among middle-aged men, and this has probably always been the case more or less. Although it may also have to do with generational and cultural changes, as we’ll touch on at the end of the article.

Men at Work

It was also popular for men to get portraits done with the guys they worked with, often while wearing their work clothes — from aprons to overalls — and holding the tools of their trade — from frying pans to hammers. That men wished to immortalize themselves alongside their “co-workers” shows how important work was to a man’s identity and the close bond men used to feel with those they shared a trade with and toiled next to.

When a photo studio wasn’t nearby, snapshots were taken. These snapshots reveal the camaraderie men felt with those they worked beside.

As the trades waned in importance, and white collar work waxed, photographs of men on the job became more formal and less intimate. Instead of seeing each as fellow craftsmen, working for a common goal with a shared pride in the work, men became competitors with each other, each trying to get ahead in a dog-eat-dog world. And a lot less work-related photographs were taken in general. Perhaps because we only take photographs of pleasurable things, things we want to always remember, and the pleasure men took in their work had fallen.

Men on the Field

As team sports became one of the great passions of a man’s life in the 1890s, the team photo became a required ritual. A team wished to have a memento of the exploits of the season, and no yearbook was complete without one. The changing poses of the team photo provide a window into the evolving mores of male affection, and perhaps into the evolving nature of sport itself.

At the turn of the century, team photos were more intimate and casual, with teammates piling on top of one another, leaning on each other, and draping their arms around one another.

Starting in the 1920s, team photos became more formal, more like the team photos we know today. Instead of touching each other, the men crossed their arms across their stomach or put them behind their backs. Each player stood more isolated from the others, much as the space between businessmen had grown as well. Still a team, but a team of distinct individuals.

Men at War

Some of the most intense bonds between men have always been found among those who serve in the military. Gender segregation (at least in times past), is at its very highest. Men are far from home and can only rely on each other; together they face the highest dangers and are motivated less by duty to country and more by the desire not to let their brothers down. Serving is such an unquestionably manly thing, that homophobia dissipates; soldiers care less about one’s sexuality than whether the man can get the job done.

The man who served in WWII and experienced intense camaraderie with his battlefield brothers, often had trouble adjusting to life back home, in which he got married, settled in the suburbs, and felt cut off and isolated from other men and the kind of deep friendships he had enjoyed during the war.

(Picturing Men: A Century of Male Relationships in Everyday American Photography by John Ibson, via The Art of Manliness)

The photographs, spanning from the Civil War to the 1950s, reveal a lost world. They present men of different ages, classes, and races in a range of settings: posed in photographers' studios, on beaches, in lumber camps, on farms, on ships, indoors and out. They show men comfortably sitting on each other's laps, embracing, holding hands, and expressing their various relationships through countless examples of simple physical contact.

Men as Friends

From the Civil War through the 1920s, it was very common for male friends to visit a photographer’s studio together to have a portrait done as a memento of their love and loyalty. Photographers would offer various backgrounds and props the men could choose from to use in the picture. Sometimes the men would act out scenes; sometimes they’d simply sit side-by-side; sometimes they’d sit on each other’s laps or hold hands. The men’s very comfortable and familiar poses and body language might make the men look like gay lovers to the modern eye — and they could very well have been — but that was not the message they were sending at the time. The photographer’s studio would have been at the center of town, well-known by everyone, and one’s neighbors would having been sitting in the waiting room just a few feet away. Because homosexuality, even if thought of as a practice rather than an identity, was not something publicly expressed, these men were not knowingly outing themselves in these shots; their poses were common, and simply reflected the intimacy and intensity of male friendships at the time — none of these photos would have caused their contemporaries to bat an eye.

When the author of Picturing Men, John Ibson, conducted a survey of modern day portrait studios to ask if they had ever had two men come in to have their photo taken, he found that the event was so rare that many of the photographers he spoke to had never seen it happen during their career.

Snapshots

When portable cameras for the amateur photographer became more widely available, they allowed men to photograph themselves in a greater range of more spontaneous situations, and the practice of sitting for formal portraits together waned in the 1930s. The snapshots usually were developed by someone else who would have gotten a look at all of them, so again, these pictures were not likely purposeful expressions of gay love, but rather captured the very common level of comfort men felt with one another during the early 20th century.

One of the reasons male friendships were so intense during the 19th and early 20th centuries, is that socialization was largely separated by sex; men spent most their time with other men, women with other women. In the 1950s, some psychologists theorized that gender-segregated socialization spurred homosexuality, and as cultural mores changed in general, snapshots of only men together were supplanted by those of coed groups.

After WWII, casually touching between men in photographs decreased precipitously. It first vanished among middle-aged men, but lingered among younger men. But in the 50s, when homosexuality reached its peak of pathologization, eventually they too created more space between themselves, and while still affectionate began to interact with less ease and intimacy.

It’s not true that American men are no longer affectionate with each other at all. Hand-holding and lap-sitting are out, but putting your arms around your buddies is still common. Physical affection seems more common among high school and college age men, a time when friendships are closer, than among middle-aged men, and this has probably always been the case more or less. Although it may also have to do with generational and cultural changes, as we’ll touch on at the end of the article.

Men at Work

It was also popular for men to get portraits done with the guys they worked with, often while wearing their work clothes — from aprons to overalls — and holding the tools of their trade — from frying pans to hammers. That men wished to immortalize themselves alongside their “co-workers” shows how important work was to a man’s identity and the close bond men used to feel with those they shared a trade with and toiled next to.

When a photo studio wasn’t nearby, snapshots were taken. These snapshots reveal the camaraderie men felt with those they worked beside.

As the trades waned in importance, and white collar work waxed, photographs of men on the job became more formal and less intimate. Instead of seeing each as fellow craftsmen, working for a common goal with a shared pride in the work, men became competitors with each other, each trying to get ahead in a dog-eat-dog world. And a lot less work-related photographs were taken in general. Perhaps because we only take photographs of pleasurable things, things we want to always remember, and the pleasure men took in their work had fallen.

Men on the Field

As team sports became one of the great passions of a man’s life in the 1890s, the team photo became a required ritual. A team wished to have a memento of the exploits of the season, and no yearbook was complete without one. The changing poses of the team photo provide a window into the evolving mores of male affection, and perhaps into the evolving nature of sport itself.

At the turn of the century, team photos were more intimate and casual, with teammates piling on top of one another, leaning on each other, and draping their arms around one another.

Starting in the 1920s, team photos became more formal, more like the team photos we know today. Instead of touching each other, the men crossed their arms across their stomach or put them behind their backs. Each player stood more isolated from the others, much as the space between businessmen had grown as well. Still a team, but a team of distinct individuals.

Men at War

Some of the most intense bonds between men have always been found among those who serve in the military. Gender segregation (at least in times past), is at its very highest. Men are far from home and can only rely on each other; together they face the highest dangers and are motivated less by duty to country and more by the desire not to let their brothers down. Serving is such an unquestionably manly thing, that homophobia dissipates; soldiers care less about one’s sexuality than whether the man can get the job done.

The man who served in WWII and experienced intense camaraderie with his battlefield brothers, often had trouble adjusting to life back home, in which he got married, settled in the suburbs, and felt cut off and isolated from other men and the kind of deep friendships he had enjoyed during the war.

(Picturing Men: A Century of Male Relationships in Everyday American Photography by John Ibson, via The Art of Manliness)

.jpg)

0 comments:

Post a Comment